Blam engine: Difference between revisions

From Halopedia, the Halo wiki

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Disambig header|the game engine|the codename for ''[[Halo: Combat Evolved]]''|Blam!}} | |||

---- | |||

{{Status|RW}} | {{Status|RW}} | ||

{{Stub}} | {{Stub}} | ||

{{ | {{Infobox/Engine | ||

|name=Blam engine | |||

|image= | |||

|othernames= | |||

*Blam! engine | |||

*''Halo'' engine | |||

|developer=[[Bungie]] | |||

|entereddev=[[1997]] | |||

|derivatives= | |||

*[[#Saber3D hybrid engine|Saber3D hybrid engine]] | |||

*[[#Tiger Engine|Tiger Engine]] | |||

*[[Slipspace Engine]] | |||

|firstuse=''[[Halo: Combat Evolved]]'' (2001) | |||

|latestuse=''[[Halo 5: Guardians]]'' (2015) | |||

}} | |||

The '''Blam engine''',{{Ref/Site|Id=TigerEngine|URL=https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1022106/Lessons-from-the-Core-Engine|Site=GDC Vault|Page=Lessons from the Core Engine Architecture of Destiny|D=22|M=9|Y=2021}} often stylised '''Blam! engine''' and alternatively known as simply the '''''Halo'' engine''', is the [[Wikipedia:Game engine|game engine]] that powers the majority of ''[[Halo (disambiguation)|Halo]]'' titles, beginning with ''[[Halo: Combat Evolved]]'' in [[2001]]. It has since been succeeded by the [[Slipspace Engine]] in [[2021]], with the release of ''[[Halo Infinite]]''. | The '''Blam engine''',{{Ref/Site|Id=TigerEngine|URL=https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1022106/Lessons-from-the-Core-Engine|Site=GDC Vault|Page=Lessons from the Core Engine Architecture of Destiny|D=22|M=9|Y=2021}} often stylised '''Blam! engine''' and alternatively known as simply the '''''Halo'' engine''', is the [[Wikipedia:Game engine|game engine]] that powers the majority of ''[[Halo (disambiguation)|Halo]]'' titles, beginning with ''[[Halo: Combat Evolved]]'' in [[2001]]. It has since been succeeded by the [[Slipspace Engine]] in [[2021]], with the release of ''[[Halo Infinite]]''. | ||

| Line 76: | Line 92: | ||

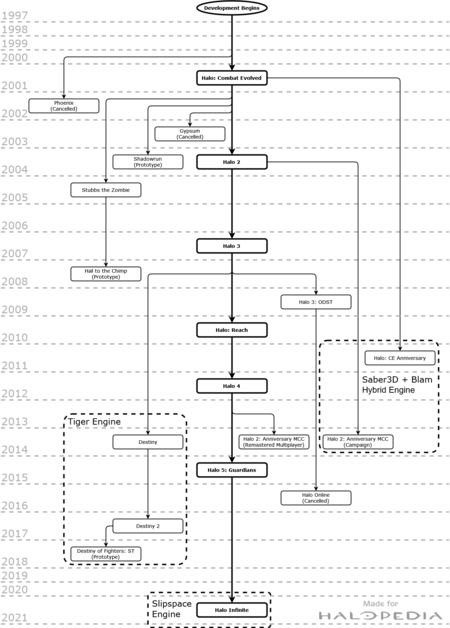

==Gallery== | ==Gallery== | ||

===Flow charts=== | |||

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

File:HP Diagram BlamHistory-Simple.png|A simplified version of the development history of the Blam engine. | |||

File:HP Diagram BlamHistory-Normal.png|A larger version of the previous flow chart, including the development history of the ''Halo: CE'' and ''Halo 2'' ports. | File:HP Diagram BlamHistory-Normal.png|A larger version of the previous flow chart, including the development history of the ''Halo: CE'' and ''Halo 2'' ports. | ||

File:HP Diagram BlamHistory-Full.png|A further expanded version of the flow chart, including all ''Halo'' game ports. | File:HP Diagram BlamHistory-Full.png|A further expanded version of the flow chart, including all ''Halo'' game ports. | ||

</gallery> | |||

===Development screenshots=== | |||

<gallery> | |||

File:H5G Prerelease Sprint-PistolPolyCounts.png|A side-by-side image of the [[M6D magnum]] from ''Combat Evolved'' and [[M6H magnum|M6H2 magnum]] from ''Halo 5: Guardians'', highlighting the increase in poly count. | |||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Revision as of 05:55, January 22, 2022

This article is a stub. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

This article is a stub. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

| Blam engine | |

|---|---|

|

Also known as: |

|

|

Developed by: |

|

|

Entered development: |

|

|

Derivative engines: |

|

|

First use: |

Halo: Combat Evolved (2001) |

|

Latest use: |

Halo 5: Guardians (2015) |

The Blam engine,[1] often stylised Blam! engine and alternatively known as simply the Halo engine, is the game engine that powers the majority of Halo titles, beginning with Halo: Combat Evolved in 2001. It has since been succeeded by the Slipspace Engine in 2021, with the release of Halo Infinite.

Development history

This section needs expansion. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

This section needs expansion. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

According to Chris Butcher, an engineering director at Bungie, the Blam engine entered development in 1997 alongside the game that would come to be Halo: Combat Evolved. Each successive Halo game developed by Bungie was built upon the Blam engine, and it was significantly evolved with each successive game.[1]

Derived engines

Slipspace Engine

- Main article: Slipspace Engine

This section needs expansion. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

This section needs expansion. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

The Slipspace Engine is a heavily revamped and modernised game engine developed by 343 Industries, which is derived from Blam. While containing significant amounts of new and overhauled code, the engine is ultimately based upon the version of Blam used in Halo 5: Guardians and still retains remnants of this engine.[2] Halo Infinite will be the first game to utilise the Slipspace Engine, and it will presumably succeed the Blam engine as the engine of choice for future Halo titles.[3]

Saber3D hybrid engine

- Main article: Saber3D engine

This section needs expansion. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

This section needs expansion. You can help Halopedia by expanding it.

One of the key design goals of the Anniversary remasters of Halo: CE and Halo 2 was to leave the titles' original gameplay completely untouched, so that the games would play exactly as they originally did. As a result, both Halo: Combat Evolved Anniversary and Halo 2: Anniversary use their respective game's original engine. However, in order to produce the remastered anniversary graphics, developer Saber Interactive needed a significantly more modern rendering engine. Thus, for each of the games, they retrofitted their own internally-developed engine, the Saber3D engine, onto the original engine to facilitate the remastered graphics, while preserving the original Blam engine's gameplay logic so that the games play exactly as they originally did. This has been compared to essentially running two game engines at once, within the same game. This unique design also allowed for the ability for the player to switch between the two graphical modes at any time within the gameplay.[citation needed]

Tiger Engine

The Tiger Engine was a significantly overhauled version of the Blam engine developed for the Destiny franchise by Bungie, after their split from Microsoft. It was designed to overcome a number of limitations with the Blam engine and to be future-proofed for the then-upcoming eighth console generation. Both Destiny and Destiny 2 were developed using the engine.[1]

The Tiger Engine was a response to a number of constraints of the Blam engine that were becoming increasingly problematic as time passed, and both video game hardware and the industry evolved. Rather than technical debt or messy code, these constraints were mainly a result of the core design principles of the Blam engine - for instance, Blam assumed that there would only be one target platform for its games, and was largely single-threaded. As Bungie continued to iterate upon the Blam engine with each subsequent game, more and more code was built upon these fundamental assumptions, turning them essentially into "unwritten rules" of the engine.[1]

These constraints were not compatible with Destiny in a number of ways: it was a multi-platform game targetting release on a multitude of consoles, all of its target platforms contained multi-core processors which requires multithreading to take full advantage of, and finally, Destiny would feature many sizable content updates after launch, which Blam did not support. However, Bungie still wanted to preserve large portions of the Blam engine, notably the gameplay framework and networking code, and so couldn't build a new engine or switch to a third-party one.[1]

Thus, a team of engineers was formed within Bungie to develop the Tiger Engine. In 2008, they forked the codebase of the then in-development Halo: Reach, and began to work on exhaustively overhauling the majority of the engine to alleviate the highlighted constraints. The team worked steadily on the Tiger Engine for more than five years, excluding a 5-month hiatus in 2010 when they briefly rejoined the Halo: Reach engineering team to help ship the game. In 2011, after the release of Reach, the former Reach engineering team then joined the Destiny project and contributed further to the development of the Tiger Engine. By mid-2012, the engine had progressed to a state where the art and level design teams could begin producing art assets and designing missions, respectively, and by the end of 2013, Destiny was fully playable on all platforms, leaving only optimisation and polish work to be done on the Tiger Engine, before the game's launch in 2014.[1]

Games using the Blam engine

Released games

The following games were released on the Blam engine, or a descendant of it:

- Halo: Combat Evolved (2001)

- Halo: Combat Evolved for PC (2003)

- Halo: Combat Evolved for Macintosh (2003)

- Halo: Custom Edition (2004)

- Halo: Combat Evolved Anniversary (2011) (Saber3D hybrid engine)

- Halo 2 (2002)

- Halo 2 for Windows Vista (2007)

- Halo 2: Anniversary (2014) (Saber3D hybrid engine)

- Stubbs the Zombie in Rebel Without a Pulse (2005)

- Halo 3 (2007)

- Halo 3: Mythic (2009)

- Halo 3: ODST (2009)

- Halo: Reach (2010)

- Halo 4 (2012)

- Destiny (2014) (Tiger Engine)

- Halo: The Master Chief Collection (2014) (Engine version depends upon game)

- Halo 5: Guardians (2015)

- Halo 5: Forge (2016)

- Destiny 2 (2017) (Tiger Engine)

- Halo Infinite (2021) (Slipspace Engine)

Cancelled projects

These games were developed on the Blam engine but ultimately cancelled before release.

- Phoenix (cancelled in late 2002 or early 2003)

- Gypsum (cancelled in June 2003)

- Halo Online (cancelled in 2016)

Prototypes

Multiple games have also been prototyped using the Blam engine:

- Shadowrun (2007)[4] (Final game did not use Blam)

- Hail to the Chimp[5][6] (2008) (Final game did not use Blam)

- Destiny of Fighters: Super Turbo[7] (2018) (Tiger Engine; unreleased; internal Bungie game jam project)

Gallery

Flow charts

Development screenshots

A side-by-side image of the M6D magnum from Combat Evolved and M6H2 magnum from Halo 5: Guardians, highlighting the increase in poly count.

Sources

- ^ a b c d e f GDC Vault, Lessons from the Core Engine Architecture of Destiny (Retrieved on Sep 22, 2021) [archive]

- ^ Mixer: Halo December 19, 2018 stream

- ^ Halo Waypoint, Our Journey Begins (Retrieved on Sep 22, 2021) [archive]

- ^ YouTube - Gamecheat13, Shadowrun Halo Prototype - The Artifact Playthrough

- ^ Twitter, @ihatecompvir (Retrieved on Sep 23, 2021) [archive]

- ^ Twitter, Zeddikins (@zeddikins) (Retrieved on Sep 23, 2021) [archive]

- ^ David Candland, Functional Prototypes (Retrieved on Jan 18, 2022) [archive]

|

| |||||||||||