Prowler

From Halopedia, the Halo wiki

Prowlers, sometimes nicknamed "bats" by UNSC personnel,[1] are a specialized form of stealth-capable corvette within the UNSC Navy.[2][3] Prowlers are used by the UNSC Navy for stealth infiltration/exfiltration, electronic intelligence gathering, and minelaying operations. Prowlers are exclusively operated by Office of Naval Intelligence personnel serving under the Prowler Corps.[4][5] Most prowlers are designated with the hull classification symbol PRO, followed by a numeric designation.[6]

Overview

Role

The prowler's primary role is to stay hidden while safely gathering battlefield intelligence, avoiding direct combat due to its light weapons and armor. Because of their tactical value and potential to change the outcome of any given combat situation, every UNSC battle group has at least one prowler assigned to its ranks.[7] The prowler's standing orders to observe and record, even in the face of UNSC defeat, mean that the ships are explicitly ordered to ignore lifepods and rescue beacons.[5]

The prowler's only combat role, besides active combat monitoring and recording, is discreetly laying cloaked fields of Hornet and Moray nuclear mines in orbital regions.[7] They may also be used to drop Slipspace guidance beacons in advance of a large UNSC fleet movement, allowing a given fleet to execute in-system jumps with much more precision than they may otherwise be able to.[8] In addition, these covert roles mean that the ships are also well-suited to ferrying ONI strike teams and cargos of nuclear weapons behind enemy lines, to covertly plant in heavily-defended staging areas and invasion beachheads. Unfortunately, these missions were nevertheless typically one-way.[5] Other prowler roles include transportation for high-level commanders and prisoners.[9][10]

Design details

Prowlers are on the smaller end of the size spectrum of human starships, typically ranging a few hundred metres in length or less. The Sahara-class heavy prowler is the largest conventional prowler design operated by the UNSC, and only measures up at 281 meters (922 ft) - barely more than the Gladius-class heavy corvette. Indeed, prowlers are low-profile ships built based on corvette design principles, and are considered slow, underarmoured and underarmed for conventional fights.[11] The small nature of prowlers serves to enhance their stealth capabilities, by presenting a smaller radar cross-section and less area for thermal emissions to radiate from. An exception to this rule is the comparatively gargantuan Point Blank-class prowler; informally referred to as a "stealth cruiser" due to its size, the Point Blank measures up at 485m in length - equivalent to a Halberd-class light destroyer and twice the size of even the already-noteworthy size of the Sahara-class. Point Blank-class ships tend to serve as command-and-coordination centres and motherships for smaller prowlers on longer-ranged expeditionary strikes.[2]

Prowlers may be fitted with EMP dampers which isolate the ship's electronics in the event of electromagnetic pulse strikes.[7]

Aside from the more high-end stealth systems discussed below, prowlers may also be disguised as high-end civilian yachts, and often feature unassuming names such as the Lark, Applebee and Circumference.[12]

Stealth systems

Passive stealth systems

Prowlers avoid detection through the use of physical features designed for low observability, low-profile sensor systems, and an array of stealth systems intended to mask the ship from both visual and sensor detection.[13] Prowlers typically rely on passive stealth systems to remain undetected; ship designs employ techniques such as breaking up the thermal emissions via use of meta-materials in the hull coating known as Stealth ablative coating to break up the ship's radar signature.[5]

Active stealth systems

Prowlers may also employ expendable stealth consumables such as heat sinks designed to defer the release of thermal emissions, flares and deception jammers. These systems are typically fired out of the ship, and are thus primarily employed when stealth has failed.[5] Prowlers must have the capability to hide even from their own allies to avoid being tracked in the event a UNSC ship fell into enemy hands.[14]

Many of the aforementioned standard features were first tested on the Chiroptera-class subprowlers in the 25th century, and would later go on to become standard features in successive ONI designs.[2] However, Prowler designs deployed prior to the Human-Covenant War did not employ particularly effective active camouflage systems, and instead relied on the aforementioned passive methods to remain undetected. Future enhancements during the war and the successive reverse-engineering of Covenant and limited integration of Forerunner technology did allow for more active technologies to become standard by the late-war era and as of 2558, all prowlers employed some form of active hull camouflage technology.[9]

These more active forms of hull stealth technology encompass a variety of methods; a common form of programmable optical hull camouflage is the texture buffer, which serves to line the ship with the aforementioned photoreactive coating and allow the surface to take on similar colouration as objects behind it such as planets.[15][5] However, even these texture buffer systems were crude in comparison to Covenant active camouflage, operating on a seemingly similar principle as the SPI armor's photoreactive panels. For example, the UNSC Wink of an Eye's stealth coating was fairly unstable, making the ship waver to and from visibility uncontrollably especially when exposed to rapidly changing backgrounds, such as the clouds of a gas giant.[8] One of the later camouflage systems employed on the Sahara-class heavy prowler involves a generated field of camouflage which surrounds the ship.[16][10] These advances allowed prowlers to keep ahead of similar advancements in Covenant sensor technology.[13]

More traditional Covenant-based active camouflages and newer emission-distortion grids made their way into prowler designs in the post-war era ships, though by 2558 only a select few Winter-class prowlers had been fitted with them.[5] Active camouflage systems are limited in their usage, and can only keep the ship in stealth mode for a few minutes at a time - making their optimal usage a key consideration for planning.[15]

Engine emissions are typically masked via the use of baffler fusion drives based on Forerunner technology[13] - a type of experimental and cutting edge maneuver drive only distantly related to typical UNSC fusion engines and maintained by specific ONI maintenance teams.[5][13] These systems enable the prowler to appear to sensors the same temperature as the surrounding space, thus avoiding detection by infrared-range sensors.[17] Because prowlers inevitably release some emissions, their systems are designed distort their signatures to appear as wreckage, low-threat vessels, or even friendly craft.[13]

A prowler is able to stay stealthed for days or weeks, though the use of more active systems is limited to timeframes of a few minutes.[15] As such, they are not fully undetectable.[13] Past fifteen minutes in a combat theater, detection by Covenant sensors is noted to grow at a geometric rate.[15] If tasked with sending out reconnaissance missions, typical prowler doctrine holds that the ship is to maintain orbit above a given planet for ten to twelve hours, hiding in the darkness of the planet's terminator zone while making passive observations. However, if time is of the essence, this can be ignored - especially if the prowler commander is willing to use Pelicans or other smallcraft as distractions.[18]

Crew

- Main article: UNSC Prowler Corps

Prowlers are primarily crewed by Naval service personnel from the Office of Naval Intelligence's elusive "Prowler Corps". Prowler Corps officers begin their careers as regular naval officers, and have traditions and secrets unique to their insular clique - separating them from even the rest of ONI. Prowler crew recruitment is an unorthodox process, with no records existing of how candidates are selected or where they are trained.[5] Prowler Captains ultimately a huge influence in these selection processes and the final say in prowler recruitment - a condition exploited on one occasion by Hector Nyeto to fill his crews with Insurrectionist-sympathetic officers.[19]

Prowler commanding officers often held the rank of Captain, though these assignments were variable. In one instance, Captain Halima Ascot oversaw the entirety of Task Force Yama consisting of over a dozen prowlers, with Lieutenant Commander Nyeto holding command over the entire squadron Ghost Flight. In other instances, Captains such as Lucius Jiron and Tobias Foucault held command over only one vessel.

Prowler captains receive extensive training in the use of astronomical objects to their advantage in hiding their presence, as well as the deployment of drone networks to maintain concealment during missions.[13] There is also a tradeoff between speed and stealth, and prowler commanders are forced to walk a fine balance when optimizing their stealth systems and engine power.[11]

Sensors

Prowlers are equipped with a wide variety of sensor equipment and electronic warfare devices, many of them mounted in a sensor array located in the craft's nose[11] or in active sensor arrays fitted as large discs on the ship's dorsal surface.[9] The X-ELF radar system is a feature aboard the Sahara-class prowlers[15], though prowlers may also contain sensing technologies such as a mass spectrometer[11] and lidar.[20] The specialised refit Sahara-class prowler UNSC Port Stanley was upgraded with a high-fidelity real-time holographic mapping suite which enables the generation of highly accurate images of a given area when working in concert with the prowler's subsidiary drones and other sensors.[20]

Prowlers may be fitted with an additional complement of tactical drones for remote monitoring of other locations.[21] These systems include BLACK WIDOW communications satellites[15], baseball-sized stealth satellites capable of being used for reconnaissance.[22]

In the post-war era, advances from Covenant reverse-engineering have allowed more recent prowler designs such as the Winter-class to incorporate Hyperscanner arrays.[5]

Armament

Prowlers are among the slowest and most under-armed vessels in the UNSC fleet. As such, they have very little in the way of conventional starship munitions, and rely on their stealth systems to stay alive.[11] The most well-equipped prowlers in service, the Razor-class prowler, was equipped with M28 Shrieker missile pods and Argent V missiles, allowing it to hold its ground in a fight if needed.[2] Most prowlers were less lucky, with the Sahara and Winter close possessing no conventional missile complement at all.[2] The smaller Winter-class prowlers only hold twin M8545 machine-linked autocannons.[5]

To make up for this, prowlers are often fitted with more in the way of strategic nuclear weaponry. These range from the singular M947 Shiva and Rudra[23] nuclear missiles on the Sahara-class to the Fury tactical nuclear weapons fitted onto the Razor-class - with the latter serving as a self-destruct device should the ship be in danger of capture. Space mines - both nuclear and nonnuclear - are a common strategic armament on prowlers, with the M441 Hornet Remote Explosive System and CBU-R98 Moray mine rack featured on the Sahara and Razor-classes, respectively.[2][5] Nuclear weapons storage aboard a prowler is a risky tradeoff; the storage of nukes aboard the prowler in slipspace will make it impossible to maintain stealth when exiting slipstream as the nuclear weapons emit a detectable Cherenkov radiation flare upon transition back to realspace. If stealth is of the utmost priority, a prowler may be forced to jettison its nuclear payload while in slipspace as to remain undetected.[11]

In addition to the lack of conventional munitions, prowlers more commonly equip more advanced weapon systems such as directed-energy weapons. An EMP cannon, the XEV9-Matos, is fitted on the Sahara-class as a powerful weapon capable of disabling a target for boarding.[9] The Winter-class is fitted with three M995 Backstop point defense laser turrets for its own defense.[2]

Classes

Known classes

- Eclipse-class prowler

- Razor-class prowler

- Winter-class prowler

- Sahara-class heavy prowler

- Point Blank-class prowler

Unknown class

- Unidentified stealth ship – At least one under construction aboard Argent Moon as of 2558.

- Unidentified heavy Prowler class - An unidentified classification of heavy prowler employed in the post-war era.

- Unidentified prowler class – An unidentified prowler classification seen fairly often.

- Unidentified smaller class – A smaller prowler class employed in the early war.

- Last gleaming.png

Subprowlers

"Subprowler" is an informal designation for a smaller stealth-capable spacecraft – often deployed by larger prowlers – that are used to infiltrate and exfiltrate personnel and cargo from planetary surfaces in a role not dissimilar to dropships. Though designed with low-observable technologies, subprowlers also feature a series of electronic countermeasures and decoy capabilities that increase their survivability in the dangerous period when entering and exiting atmospheres, or when operating near advanced aerospace defenses.[13] These can work by altering the subprowler's profile to resemble more common cargo shuttles and transports on sensor networks.[2]

Subprowlers are generally not fitted with slipspace drives, though this is not a hard-and-fast rule; Chiroptera-class subprowlers were a notable exception to this rule, and operated compact - relative to the era - FTL drives. However, they were an exception to the typical rule, and often faced maintenance and mission expectations and threat profiles far different to what their successors would encounter.[24]

The Pelican dropships Tart-Cart and Bogof were modified in many respects to suit the role of subprowlers - though the role of stealth dropships are nonetheless removed from that of a subprowler.[24] The D102 Owl dropship was created in part to fulfill a niche between full subprowlers and more common dropships like the Pelican - a stealth-capable insertion shuttle that can be more widely employed across the United Nations Space Command armed forces without needing as much specialised maintenance.[25]

- Black Cat-class subprowler – Small exfiltration ships used mostly as exfiltration craft to escape combat situations with stealth and ease, and have slipspace capacitor of limited use.

- Chiroptera-class subprowler – Early 25th century-era testbed for many of the stealth technologies that would later become standard across prowlers as a whole.

- U81 Condor – Condor variant occasionally classed as a subprowler due to its covert mission focus, despite lacking the specialised stealth technology characteristic of true subprowlers.

Gallery

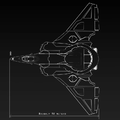

An early unused design for Soren's ship in Halo: The Television Series, in which it was supposed to resemble a UNSC prowler.

List of appearances

|

|

Sources

- ^ Halo: Silent Storm, chapter 10

- ^ a b c d e f g h Halo Encyclopedia (2022 edition), page 128-129

- ^ Halo Encyclopedia (2009 edition), page 263

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, chapter 18

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Halo: Warfleet, page 46-47

- ^ Halo Mythos, page 140

- ^ a b c Halo: Ghosts of Onyx, chapter 35

- ^ a b Halo: Evolutions - The Impossible Life and the Possible Death of Preston J. Cole

- ^ a b c d Halo 4: The Essential Visual Guide, page 190

- ^ a b Halo 4 - Spartan Ops, episode Catherine

- ^ a b c d e f Halo: Ghosts of Onyx, chapter 22

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, chapter 28

- ^ a b c d e f g h Halo Waypoint, ONI Prowler (Retrieved on Jan 19, 2021) [archive]

- ^ Halo: The Thursday War, chapter 13

- ^ a b c d e f Halo: Ghosts of Onyx, chapter 32

- ^ Halo Legends - The Package (animated short)

- ^ Halo: Ghosts of Onyx, chapter 2

- ^ Halo: Oblivion, chapter 6

- ^ Halo: Silent Storm, chapter 25

- ^ a b Halo: Mortal Dictata, chapter 10

- ^ Halo: Silent Storm, chapter 14

- ^ Halo: Ghosts of Onyx, chapter 40

- ^ Halo: The Thursday War, chapter 13

- ^ a b Halo Waypoint, Canon Fodder - Encyclopedia Extravaganza (Retrieved on Jun 1, 2022) [archive]

- ^ Halo Encyclopedia (2022 edition), page 150

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||