Fusion drive

From Halopedia, the Halo wiki

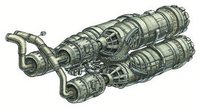

The fusion drive,[1] also known as a fusion engine,[2][3] is a type of spacecraft maneuver drive[4] which serves as the primary form of sublight propulsion on most human spacecraft, whereas the Shaw-Fujikawa Translight Engine is used for travel at superluminal, or faster-than-light, speeds. The fusion drive system generates both power and direct thrust for the ship.[5]

Description[edit]

The primary component of a fusion drive is an inertial electrostatic fusion reactor or a series of such reactors. The reactors on UNSC warships fuse Deuterium and Helium-3 atoms[5] to generate a stable and abundant supply of superheated plasma within a magnetic containment field.[2] The plasma is channeled into a series of exhaust manifolds, which vector it out of the ship's engine nozzles along with added water or hydrogen reaction mass to provide propulsion for the ship.[5] The drive system utilizes inertial-electrostatic containment and higher-order manifolds to mitigate fusion backblast,[6] while magnetic fields and thrust-vectoring plates are used to improve maneuverability.[5]

The main components of the fusion drive are typically located in a ship's engineering.[2] The number of fusion engines varies between ship classes. UNSC frigates are typically equipped with two primary reactors[7] and at least another two secondary reactors,[8] while Halcyon-class light cruisers are powered by an array of three fusion reactors.[9] Larger ships, such as the mobile hospital UNSC Hopeful, could possess as many as six reactors.[10] The number of engine exhausts also varies greatly; ships usually have two or more primary adjacent exhaust nozzles, and a series of smaller, secondary ones.

Fusion engines are capable of producing remarkable acceleration; using gravity-assist maneuvers to an advantage, human ships—from small diplomatic shuttles to Halcyon-class cruisers—are capable of crossing interplanetary distances in less than an hour.[11][12]

For small-scale maneuvering, human ships utilize smaller chemical rocket thrusters placed around the vessel. Such thrusters expel chemical propellants such as triamino hydrazine.[13]

Development history[edit]

Significant developments were made in fusion engine technology over the course of the 26th century; the Mark II Hanley-Messer fusion engines used by Halcyon-class cruisers produced only a tenth of the power output of modern reactors as of 2552.[14]

In 2552, the UNSC Pillar of Autumn was refit with a power plant which used an experimental architecture where a single main reactor was nestled within two smaller reactor rings. When activated, the secondary reactors supercharged the main reactor, and their overlapping magnetic fields could temporarily boost the reactor output by 300 percent. In addition, the engine did not require external coolant systems like most reactors, instead neutralizing waste heat by means of a "laser-induced optical slurry of ions chilled to near-absolute zero". The more power the reactor was generating, the more supercooled particles it produced, effectively cooling itself.[15]

Known models[edit]

Mark II Hanley-Messer DFR[edit]

The Mark II Hanley-Messer DFR is a type of deuterium fusion power plant used on Halcyon-class light cruisers, which are typically equipped with three of the reactors.[16] These fusion drives are designed for bulk maneuvering rather than speed.[17] They were obsolete by 2552, providing only a tenth of the power generated by modern reactors at the time.[14]

Naoto Technologies: V4/L-DFR[edit]

Manufactured by Naoto Technologies,[18] the V4/L-DFR is a deuterium fusion drive equipped on Charon-class light frigates, such as UNSC Forward Unto Dawn.[19]

XR2 Boglin Fields: S81/X-DFR[edit]

Manufactured by Boglin Fields,[18] the S81/X-DFR is an advanced type of fusion drive serving as the primary sublight engine of the experimental warship UNSC Infinity.[19][20] Unlike most deuterium fusion drives of human design, the S81/X-DFR is classified as a form of repulsor engine.[21] Massive in size, this engine module took fifteen years to design, build, and test.[22]

Boglin Fields Starfire-IV fusion rockets[edit]

Manufactured by Boglin Fields, two Starfire-IV fusion rockets were installed on the UNSC Pillar of Autumn as part of the ship's refit for Operation: RED FLAG in 2552.[23]

OKB Karman 56K fusion drives[edit]

Manufactured by OKB Karman, two 56K fusion drives were used by the UNSC In Amber Clad.[24]

Orphios Energy Systems Jupiter-1[edit]

Manufactured by Orphios Energy Systems, six Jupiter-1 maneuver drives were used by the UNSC Spirit of Fire. These were salvaged from the destroyer UNSC Calcutta and put in the Spirit in 2530.[25]

TANITH TKOFZ-2 Fusion Rockets[edit]

Four TKOFZ-2 fusion rockets were used by the Able-class heavy destroyers.[26]

Use as improvised weapons[edit]

Fusion drives can also be used as improvised weapons of mass destruction. A ship's captain possesses the codes necessary to initiate fusion core overload in their command neural interface, but reactor destabilization can also be initiated manually. Though the fusion reactors are protected by magnetic containment fields which surround the fusion cells, they can be destabilized by explosive ordnance once the exhaust couplings protecting the reactor vents have been retracted. Significant amount of damage to the engines will trigger a "wildcat destabilization". The reactor will then detonate within minutes, generating a temperature of nearly 100,000,000 degrees. The most notable instance of this was when John-117 destroyed Installation 04 by overloading the fusion reactors of the UNSC Pillar of Autumn.[2] The explosion was later revealed to be similar to a supernova to the point that it created a new element on a surviving shard of the ring.[27]

Trivia[edit]

- There are inconsistencies in the potency of the UNSC's fusion drives between a few visual scenes and other sources:

- The Fall of Reach states quite clearly that a UNSC destroyer with its engines at 66% power is incapable of accelerating out of Sigma Octanus IV's ~0.5 g gravity well, and that fighting near a gravity well in general is considered crippling for UNSC vessels.[28] First Strike also states that a UNSC frigate's reactors, and thus the drives they power, have power output in the gigawatt range, consistent with fairly low accelerations.[29] Several other scenes in the novels allude to this being the case, such as when the UNSC Iroquois accelerates at full speed for at least several seconds and still ends up below the hypervelocity floor (about 3 km/s), given the lack of explosive vaporization of the hull when it collides with a small Covenant ship.[30] Additionally, most visual depictions of space battles, such as the opening of Halo 2, The Package, and Halo: The Fall of Reach - The Animated Series depict UNSC ships as either static or slowly drifting in combat, rather than being able to casually clear their lengths in a few seconds in order to dodge projectiles that consistently take at least that long to reach them. These are all consistent with the repeated mentions that the UNSC's reactors utilize deuterium fusion.

- However, when the 478-meter UNSC In Amber Clad pursues the Solemn Penance, it's shown to clear its own length in less than a second starting from a velocity of zero, putting its acceleration at over 100 g.[31] Despite using a fusion torch for propulsion, the ship also notably does not display any back-blast, which would be extremely hazardous to the city of New Mombasa below.

- Kenneth Peters commented on the inconsistencies during a behind-the-scenes video for the development of Halo: Warfleet. He noted that, given that UNSC ships don't burn up the atmospheres of planets when engaged in them, their accelerations could not possibly be stupendously high. He also talked about the unintended consequence of unpublished figures giving UNSC ships sustained accelerations of 30 g, namely that such speeds would allow them to be used for "vaporizing planets" if they simply accelerated for an appreciable time in the direction of one. He went on to say that for these reasons, 343i decided not to give official acceleration figures for warships.[32]

List of appearances[edit]

- Halo: The Fall of Reach (First appearance)

- Halo: Combat Evolved

- Halo: The Flood

- Halo: First Strike

- Halo 2

- Halo: Ghosts of Onyx

- Halo 3

- Halo: Contact Harvest

- Halo: The Cole Protocol

- Halo Wars Genesis

- Halo Wars

- Halo: Helljumper

- Halo 3: ODST

- Halo: Evolutions - Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

- Halo: Blood Line

- Halo: Reach

- Halo: Fall of Reach

- Halo: Glasslands

- Halo: Combat Evolved Anniversary

- Halo: The Thursday War

- The Commissioning

- Halo 4: Forward Unto Dawn

- Halo 4

- Halo: Escalation

- Halo 2: Anniversary

- Hunt the Truth

- Halo: Fleet Battles

- Halo 5: Guardians

- Halo: The Fall of Reach - The Animated Series

- Halo Wars 2

Sources[edit]

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, page 16

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Halo: Combat Evolved, campaign level The Maw

- ^ Halo: The Flood, Chapter 1, page 33 (2003 paperback); page 36 (2010 paperback)

- ^ Halo: Warfleet, page 14

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Halo: Warfleet, page 33

- ^ Halo Waypoint: Reality of Halo: Plasma

- ^ Halo 2, campaign level Delta Halo ("Both engine cores have spun to zero.")

- ^ Halo: First Strike, page 275

- ^ Halo Waypoint: Data Drop 5

- ^ Halo: Ghosts of Onyx, page 97

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, pages 324-329

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, page 17

- ^ Halo: Contact Harvest, page 25

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halo: The Fall of Reach, page 238

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, page 274

- ^ Halo Waypoint: Data Drop 5

- ^ Halo Mythos, page 94

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halo 4: The Essential Visual Guide, pages 228-229

- ^ Jump up to: a b Waypoint: The Halo Bulletin: 10.10.12

- ^ UNSC Infinity schematic

- ^ Halo Mythos, page 132

- ^ Halo: Warfleet, page 42

- ^ Halo: Warfleet, page 25

- ^ Halo: Warfleet, page 37

- ^ Halo: Warfleet, page 49

- ^ Halo Waypoint, Canon Fodder - Digsite Dissection (Retrieved on Jul 28, 2023) [archive]

- ^ Halo: Nightfall

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, chapter 21.

- ^ Halo: First Strike, page 285.

- ^ Halo: The Fall of Reach, chapter 21.

- ^ Halo 2, campaign level Metropolis

- ^ An Inside Look at Halo: Warfleet – A Guide to the Spacecraft of Halo (starts 63 minutes and 8 seconds).